What is the vitality and necessity

Of clean water?

Ask the man who is ill, who is lifting

His lips to the cup.

Ask the forest.

– Mary Oliver

Water. It drew many of us to Orleans.

Our town has 50 miles of saltwater shoreline and 60 freshwater ponds — places of rare beauty and bounty where we can fish, swim, stroll, sunbathe, boat, surf, contemplate the universe, paddle, and play.

But the water we can see is only a sliver of the picture. Beneath our streets, more than 100 miles of cast-iron and ductile-iron pipes bring safe water to our homes. Different pipes take wastewater away from our homes and businesses, into septic tanks and cesspools. Yet another set of drains and pipes carries stormwater away from our roads, collects it in catch basins, then deposits it in our ponds, lakes, streams and bays.

Just last year, our brand-new wastewater collection system started taking septage (toilet water), bathing water, dish, sink and laundry water — along with everything else we put down our drains — to Orleans’ state-of-the-art wastewater treatment facility. (While the term “sewering” is often used to describe wastewater disposal, we’ve learned that the more current term is “wastewater collection” — a more accurate and holistic description of water management — so that’s what you’ll see used in this issue.)

Farther down, anywhere from 10 to 400 feet underground, there’s more water — lots more. Vast yet invisible to us, a prehistoric subterranean water system — the groundwater — is what keeps our taps flowing, our toilets flushing, our gardens growing, and our laundry clean. It’s not an overstatement to say it makes our lives possible.

Most of us rarely think about our water. Where does it come from? How does it get into our homes and businesses — and where does it go when it leaves? What is the connection between the chemicals we use and the water we drink — or swim in and fish from? What — or who — caused the recent cyanobacteria blooms in Crystal and Pilgrim Lakes?

How will our town wastewater collection system improve our water quality? And how soon? What else can we do to protect and restore our waters?

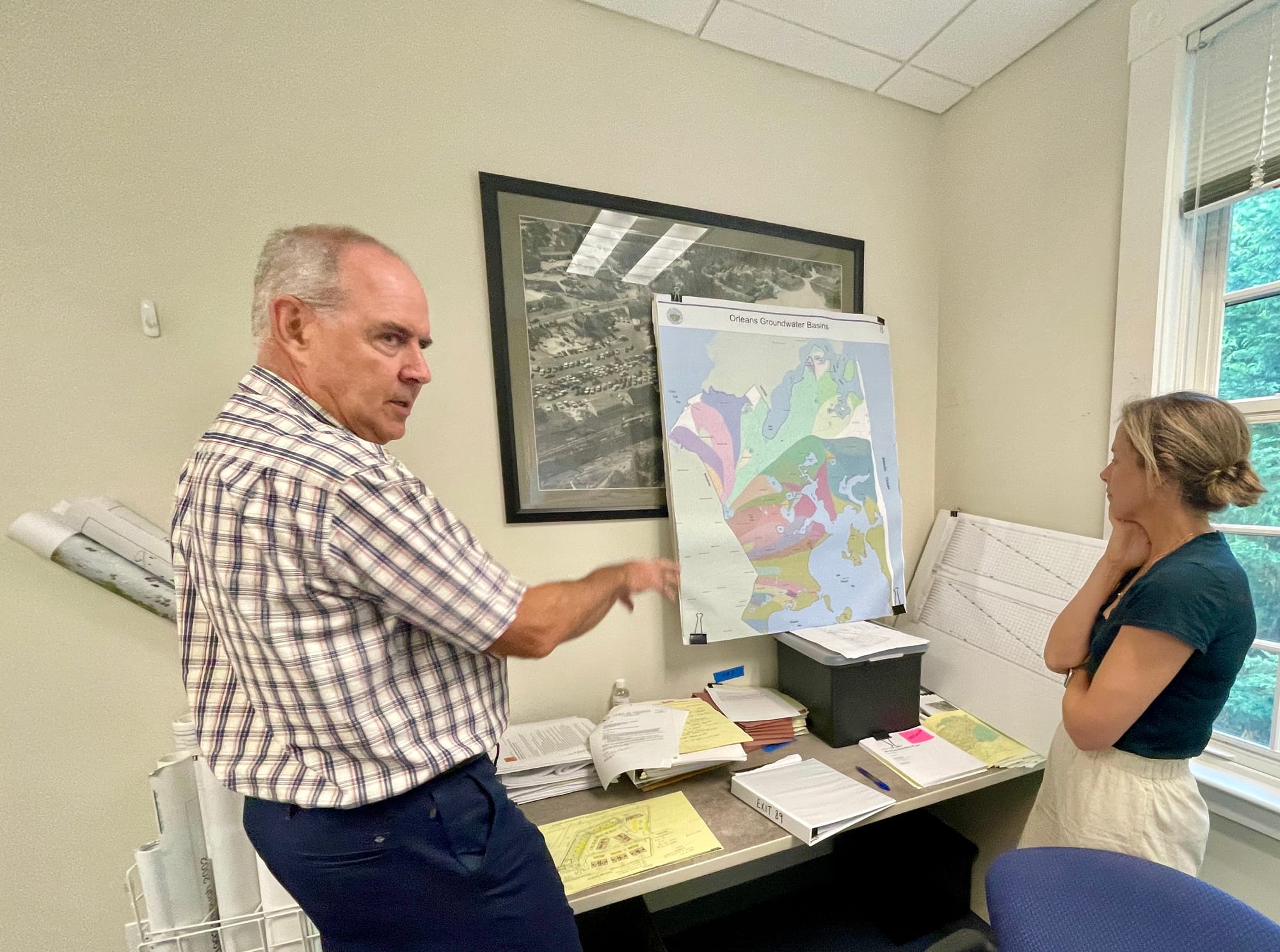

EXIT 89 wanted answers, so we hit the road. We visited the Orleans Watershed and our drinking water treatment facility. We went to Town Hall to visit the Health Department and the Planning Department. We had an enlightening tour of the town’s new wastewater treatment facility on Overland Way. We have many people to thank; you’ll find all their names at the end.

Keep reading for EXIT 89’s deep dive into the wet, wild, wonderful — and sometimes not-so-wonderful — world of Orleans water.

Hydrology 101

First, let’s cover some basics.

Cape Cod was formed more than 10,000 years ago, during the last Ice Age, when the Laurentide Ice Sheet retreated and left behind our familiar, flexed-arm-shaped spit of land composed mostly of glacial moraine — gravel, sand and silt that becomes finer and finer the farther underground you go. The Cape Cod Aquifer — the underground layers of supersaturated sand and gravel through which freshwater is constantly flowing — makes the Cape habitable.

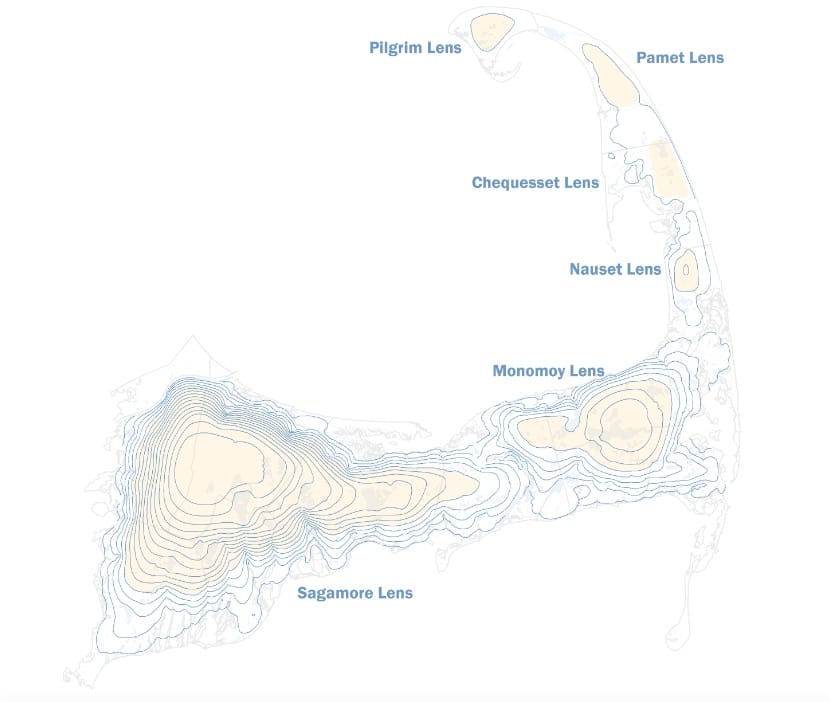

The Cape Cod Aquifer is made up of six separate “lenses” — large, convex-shaped underground areas. Picture massive, shallow bowls filled with water and sand. These six lenses are separated by tidal rivers above ground, and exist independently from one another.

Orleans sits atop the Monomoy Lens, the second largest lens within the Cape Cod Aquifer. Brewster, Chatham, Harwich, Dennis, and parts of Yarmouth and Eastham also draw water from the Monomoy Lens. How much water are we talking about? Roughly sixty million gallons flow through the Monomoy Lens each day — enough to fill 122 Olympic-sized swimming pools!

Since sand and gravel are extremely permeable, the lenses of the Cape Cod Aquifer are replenished — or in hydrology-speak, “recharged” — easily. But they are also easily contaminated, a particular concern since they are the only source of drinking water for almost all Cape Cod residents (some Falmouth drinking water comes from a surface reservoir) — both the 85 percent of us who use municipal water and the 15 percent who rely on private wells. Because of the aquifer’s fragility — and because there’s no alternative source of drinking water available — the Cape Cod Aquifer was designated in 1982 as a “Sole Source Aquifer” by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). This designation adds an additional layer of protection for the aquifer when development projects are being considered.

How does water get into our aquifer?

Precipitation. Of the 45-ish inches of rain and snow the Cape receives a year, about 40 percent will evaporate, be used by plants, or run off our lawns, patios, and roads during storms. (We’ll cover the last category, stormwater, in a bit.) The remaining 60 percent of our rainfall and snowmelt, about 27 inches a year, seeps into the ground — or “infiltrates” it — and winds up in the aquifer.

How much of the precipitation that recharges the Cape Cod Aquifer is pumped out by humans? Water usage varies, but the annual average we withdraw is about ten percent, or 10.7 billion gallons. (For a deeper plunge into our aquifer system, check out the U.S. Geological Survey’s digital models.)

Who owns the water underground?

Massachusetts owns all underground water within its borders, and grants each town a permit to withdraw the least amount of water necessary — according to population size, and defined by the Commonwealth. For Orleans, this is an average of 1.1 million gallons a day. Our population fluctuates dramatically — from about 6,000 people in winter to 20,000 or more in summer — and our usage swings between about 500,000 gallons per day in the “off” seasons to six times that, 3 million gallons, at the height of the season.

The good news is: 1) we’ve got more than enough to accommodate our needs and 2) it’s some of the best water around.

Which brings us to the Orleans Watershed.

The Orleans Watershed

In hydrology, a “watershed” — in lowercase — is a drainage basin where rainfall and snowmelt collect and travel into a common body of water. The town of Orleans has four watersheds within its boundaries — each named for the body of water it drains into: Cape Cod Bay, Nauset Estuary/Town Cove, Pleasant Bay, and the Atlantic Ocean.

The Orleans Watershed — with a capital “W” — refers to the area of land our town has been drawing its water from for the past eighty years. Before that — for centuries — people dug their own private wells to access fresh water. As the population of the Cape grew — from 47,000 year-round residents in 1950 to 222,000 in 2000, a 470% jump in five decades — hundreds of miles of pipes were laid to connect homes and businesses to municipal drinking-water supplies. Some towns resisted creating infrastructures for town water. Eastham, for example, didn’t approve a municipal water system until 2015 and Wellfleet has town water only in its business district.

Orleans took a different tack. In 1962, the the Orleans Select Board (there were only three members in those days) had the foresight to establish the Orleans Watershed — persuading voters to approve the acquisition of a 500-acre tract of land between Routes 28 and 6 in South Orleans, next to Nickerson State Park, and then to severely restrict how that land could be used in the future. Seven municipal wells were drilled there — and an eighth off Quanset Road — which together provide the drinking water used in almost all of our homes and businesses.

This large, protected tract — abutting an even larger protected area, Nickerson State Park’s 1900 acres — gives Orleans a huge leg up in keeping its drinking-water supply safe. According to Ed Eichner, Principal Water Scientist at TMDL Solutions, who has worked on Orleans water quality issues for more than 30 years, “the capture zone — the area where a town’s drinking-water wells are — is what determines the quality of the water."

Some other Cape towns haven’t been so fortunate; their “capture zones” are located near airports, military bases, gas stations, or fire stations that release chemicals into the drinking-water supply.

Orleans flushes its pipes and fire hydrants once a year — in early spring, when there are not as many people in town — to push out water that may have been sitting stagnant all winter. Flushing also helps to remove rust build-up in the iron pipes.

Who makes sure Orleans water keeps flowing — and safe to drink?

Meet Susan Brown, Assistant Superintendent of the Orleans Water Department, where she’s worked for 32 years. The Harwich native started as the business manager of the department, then was encouraged to become trained in drinking-water operations. She’s been running the water treatment plant at the Orleans Watershed since it was built in 2005. On a Friday afternoon last month, she was kind enough to show EXIT 89 around and answer our questions:

Why does our water need treating?

For starters, all municipal drinking water on the Cape is treated — primarily to meet the requirements of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), including its Lead and Copper Rule (LCR). Since the Cape’s aquifer is very acidic, and corrosive to metal piping, adjustments need to be made to keep it within a required pH level of 7.8 to 7.9.

Also, a series of coliform bacteria outbreaks in Orleans municipal water in the early 1990s led to an environmental assessment of the water quality in 1995. At Town Meetings in 2000 and 2002, residents voted to fund more thorough treatment of Orleans drinking water — primarily to remove iron and manganese, naturally occurring elements which can encourage bacteria growth. Our highly sophisticated ultrafiltration membrane water treatment plant came online in 2005.

Ultrafiltration involves pushing the water through extremely fine filters, or “membranes.” Our facility has 150 of these, which can filter a maximum total of 4.5 million gallons of water per day — far more than the 1.1 million gallons we use on average. Once the filtered water leaves the facility, it is disinfected and pumped into two storage reservoirs or water towers — one inside the watershed and one off Lots Hollow Road — which must remain sufficiently full to sustain the pressure needed to push the drinking water through 102 miles of pipes and into our homes and businesses. This is also the required minimum pressure, or pounds per square inch (PSI), for our 939 fire hydrants to deliver an adequate “fire flow” to suppress a fire.

Brown can operate the entire Orleans drinking water system from a control station on site, or remotely through an app on her phone, where she can check water usage, monitor changes in flow or pressure — like the million-gallon leak at a private home last February — or make sure there’s enough water to handle a fire. A single residential fire can require one million gallons.

You can monitor your own water use, and be alerted to possible leaks on your property, through the EyeOnWater app.

Groundwater supply levels have to be watched too. From March to September, the Water Department monitors a particular well in Nickerson State Park. If the well’s water level falls below a designated threshold, the Commonwealth issues a drought warning. Different levels of drought require different actions. Orleans also has voluntary restrictions on water use.

How clean is Orleans drinking water?

Very — thanks to our water treatment plant and the size of our protected Orleans Watershed, it consistently meets all federal and state requirements. In addition to round-the-clock testing for chlorine and correct pH that is programmed into the system, Orleans water is tested regularly for specific PFAS, also known as “forever chemicals.” (PFAS is short for “polyfluoroalkyl substances,” none of which have been found in Orleans to date.) This year, new EPA drinking water regulations require more extensive testing for 29 unregulated PFAS, as well as lithium, twice a year. This was done for the first time on August 7, 2024, and good news — none of the 29 were found.

Do climate change and sea-level rise threaten our aquifer?

Yes. Exactly how isn’t clear though, according to water scientist Ed Eichner. He explained that sea-level rise could at some point push salt water — which flows underneath freshwater, because it’s heavier — against fresh groundwater in the aquifer, and cause the water table to rise. But the predicted changes in precipitation patterns may also play a role.

“If sea-level rise causes saltwater intrusion into the aquifer, that could impact private wells, but not likely municipal drinking water wells. They are usually further from the coast,” Eichner said.

Flooding is a concern. Rising surface water and groundwater levels could impact lower-lying infrastructure, including basements, septic system leach fields, road catch basins, etc. The bottom line: “There are a lot of ‘IFs,” Eichner said. “The biggest need is to try to track the changes and adjust accordingly.”

With Every Flush

Each time you open your tap, turn on your shower, run your dishwasher, or flush your toilet, the water you use — and everything you add to it — goes down a drain.

That drain connects to a pipe which, if you’re one of the 99% of Orleans residents yet to hook up to the new wastewater collection system, takes this water/whatnot mix — also known as “wastewater” — into a septic tank on your property, or in some cases a cesspool, which is an old-fashioned DIY septic system, made by digging a hole and filling it with rocks. (It’s no longer legal to build cesspools in Massachusetts, but it’s estimated that a hundred or more still exist in Orleans.)

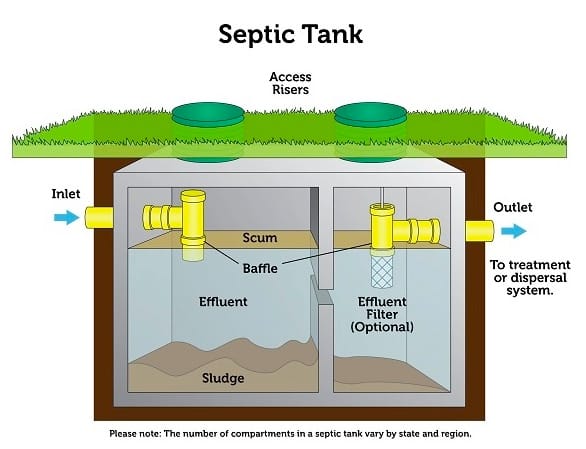

Septic tanks are large, buried concrete boxes — how large depends on the size of the system. Inside the septic tank, the solids sink to the bottom. There’s a greasy layer called scum — yes, that’s the technical term — that floats on top. The remaining liquid, or “effluent,” forms a layer in the middle. (More on this in a minute.)

The solids accumulate slowly or quickly, depending how much use the system gets. When the tank reaches capacity, it needs to be pumped out by a septic truck — or “hauler” — and taken to a treatment facility. The bulk of household and business waste is the effluent, which drains from the tank through a strategically placed perforated pipe and is then released into an underground area of the property designated as a “leach field,” where it seeps into the ground.

Some nutrients (nitrogen and phosphorus from human waste and food) are filtered out by the soil. This is why it’s so important that leach fields aren’t located too close to ponds, wetlands, or the shore. But in a town with so many waterfront homes — 635 parcels in Orleans front saltwater, 181 front freshwater, and even more contain wetlands — finding the appropriate site for a leach field can be tricky.

An average of 780,000 gallons of wastewater are released into the ground in Orleans every day. That’s a lot of wastewater for our sandy soil to absorb! And no matter where a septic system or cesspool is located, the laws of gravity and fluid dynamics ensure that some nitrogen (which causes problems in saltwater), phosphorus (which causes problems in freshwater), or other contaminants will find their way to a body of water — a wetland, pond, lake or stream, and ultimately the coast. In 2007, the Commonwealth banned the sale of household cleaning products that contain more than trace limits of phosphorus. But commercial and agricultural products containing phosphorus are still allowed.

Human waste is the biggest source of pollution — by far. Septic systems can remove as much as one-third of the nitrogen present in human urine, but what remains — and travels through the soil — is 10,000 times more concentrated than what’s considered desirable for coastal water. According to the Orleans Pond Coalition (OPC) and their extremely informative Blue Pages, a septic system serving a family of three releases enough nitrogen to contaminate hundreds of gallons of marine water — daily. A study of Meetinghouse Pond found that 69 percent of the saltwater pond’s nitrogen overload is caused by human waste. Another 14 percent is the result of fertilizer run-off.

“We live on a sandbar,” George Meservey, Orleans’ longtime Director of Planning and Community Development, likes to say, ”and every single thing that goes into the ground or down a drain will show up somewhere.”

The Cape’s steady population expansion over the last 50 years (more people = more waste) has resulted in deteriorating surface and drinking water quality. And it’s not only septage from toilets — also called “blackwater.” It’s also “greywater” — water that’s been used for washing, laundering, and bathing. Which means everything we ingest or put down our drains — Tide, Dawn, Clorox, Coppertone, Coca-Cola, Crest, OFF!, plus pharmaceuticals, like Ozempic, Xanax, and Viagra — will end up in our water.

Add climate change and warmer water temperatures to the mix, and you’ve got a recipe for major water woes: more toxic algae blooms, more red tides, more wildlife habitat loss, more bathing beach closures, and more erosion. In a nutshell, increased population has wreaked havoc on the watery world of Cape Cod. According to the Association to Preserve Cape Cod’s 2023 State of the Waters report, 90% of our coastal bays and more than a third of our freshwater ponds have “unacceptable” water quality. (More on this below.)

Where Goeth the Wastewater?

Groundwater is always moving — and, especially on the Cape, in directions you wouldn’t necessarily expect. According to Carolyn Kennedy, biologist, educator and former Chair of the Orleans Marine & Freshwater Quality Committee, “if you don’t understand how groundwater flows in this town, you don’t understand anything.”

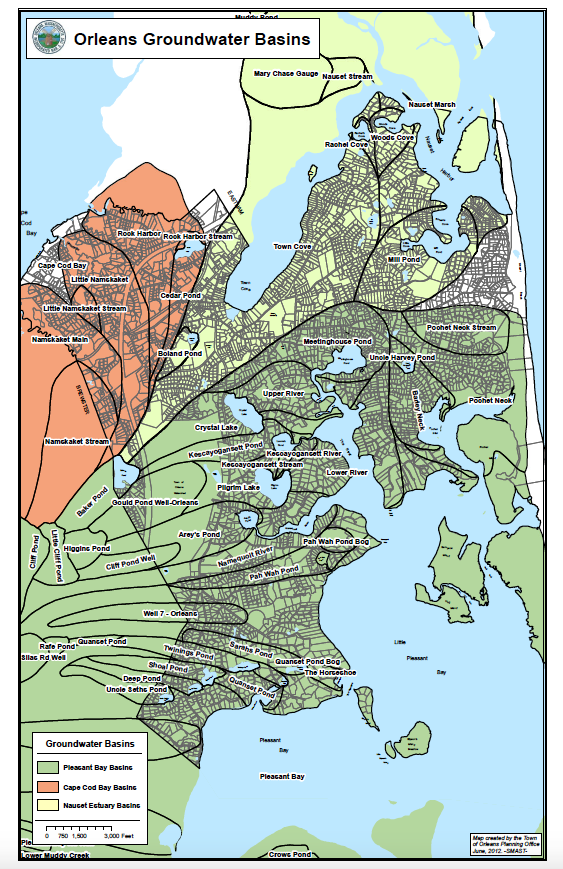

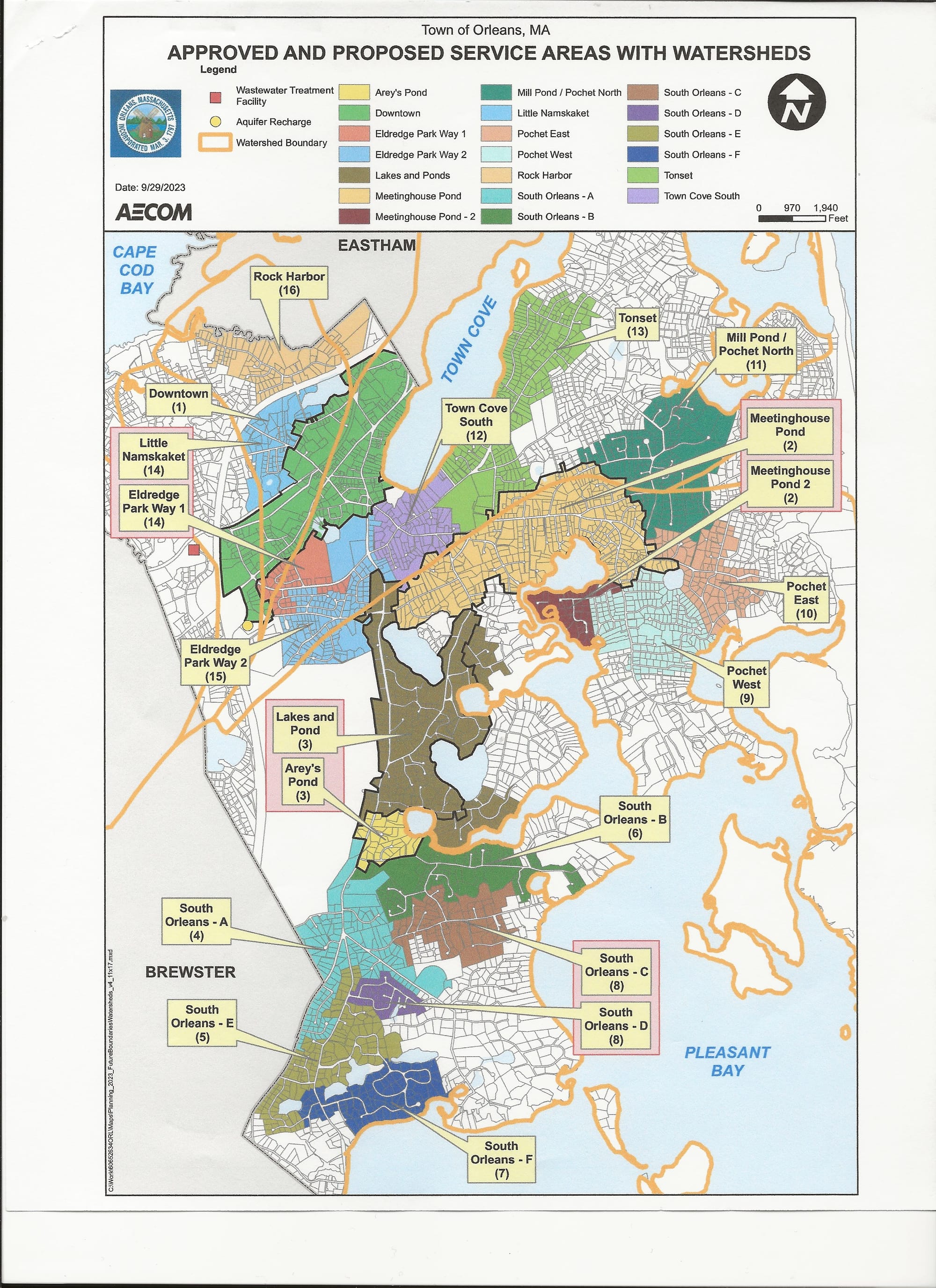

Take a look at the Orleans Groundwater Basins map, shown below. Generally speaking, groundwater in Orleans flows north and east below Route 6 and runs north and west above it.

Locate your property, then the body of water your groundwater flows toward — it might surprise you.

For example, the groundwater under a waterfront property on the west side of Pilgrim Lake flows into the lake, and relatively quickly because it’s such a short distance away. Human urine from toilet water, the primary source of phosphorus, encourages toxic algae blooms in freshwater — is particularly threatening to the surface water quality in these areas. But the groundwater under certain waterfront properties on the east side of Pilgrim Lake — and whatever pollutants it contains — doesn’t flow into the lake at all, but into The River, about half a mile to the east.

How quickly does it travel?

On Cape Cod, groundwater moves at about one-third to one foot per day. So the journey from a property on the east side of Pilgrim Lake to The River could take 10 years or more — during which the water continues to be filtered naturally. This is why wastewater system connections for properties on the west side of Pilgrim Lake, especially the parcels closest to the water — and other areas in Orleans where groundwater flows most directly into ponds and wetlands — are a priority, while connections in other areas are not. (The Town has a very cool map of approved and proposed wastewater collection system service areas in Orleans, along with their watersheds)

EXIT 89 Goes With the Flow!

Today, most Orleans properties still use septic tanks or cesspools. By 2067, when all 16 phases of our wastewater management plan are scheduled for completion, 60 percent of Orleans will be sending its wastewater to the treatment facility on Overland Road, which opened just last year.

Exit 89 was lucky enough to get a tour of the spanking-new plant from Dan Sullivan-Xenos, Project Manager with Veolia, the environmental services company contracted by Orleans to run our wastewater operations. It also has contracts with Chatham and Hyannis.

Sullivan-Xenos is energetic and welcoming — clearly proud of the shiny new facility, which boasts 42,000 linear feet of piping, able to handle up to 340,000 gallons of wastewater per day. After opening in March 2023, the flow was low — just 2,500-5,000 gallons per day. This summer, the facility was treating wastewater from 113 properties, some of which have multiple units, of the total 302 parcels slated for connection in Phase 1. That translates into an average of almost 90,000 gallons of wastewater treated per day in July — including the septage the septic-pumping companies, or “haulers,” brought in.

Fun fact: Summer Saturdays yield the highest flow of waste, due to weekend crowds and rental changeovers — all those dishes and laundry being done.

So what exactly goes down at this $47 million facility?

Let’s do some sniffing around. Speaking of which, EXIT 89 feels compelled to include a note on odor — or lack thereof: The facility is absolutely immaculate, and there’s barely a whiff of anything untoward, anywhere. It’s truly remarkable. (If you’d like a tour, contact the Orleans Wastewater Department.)

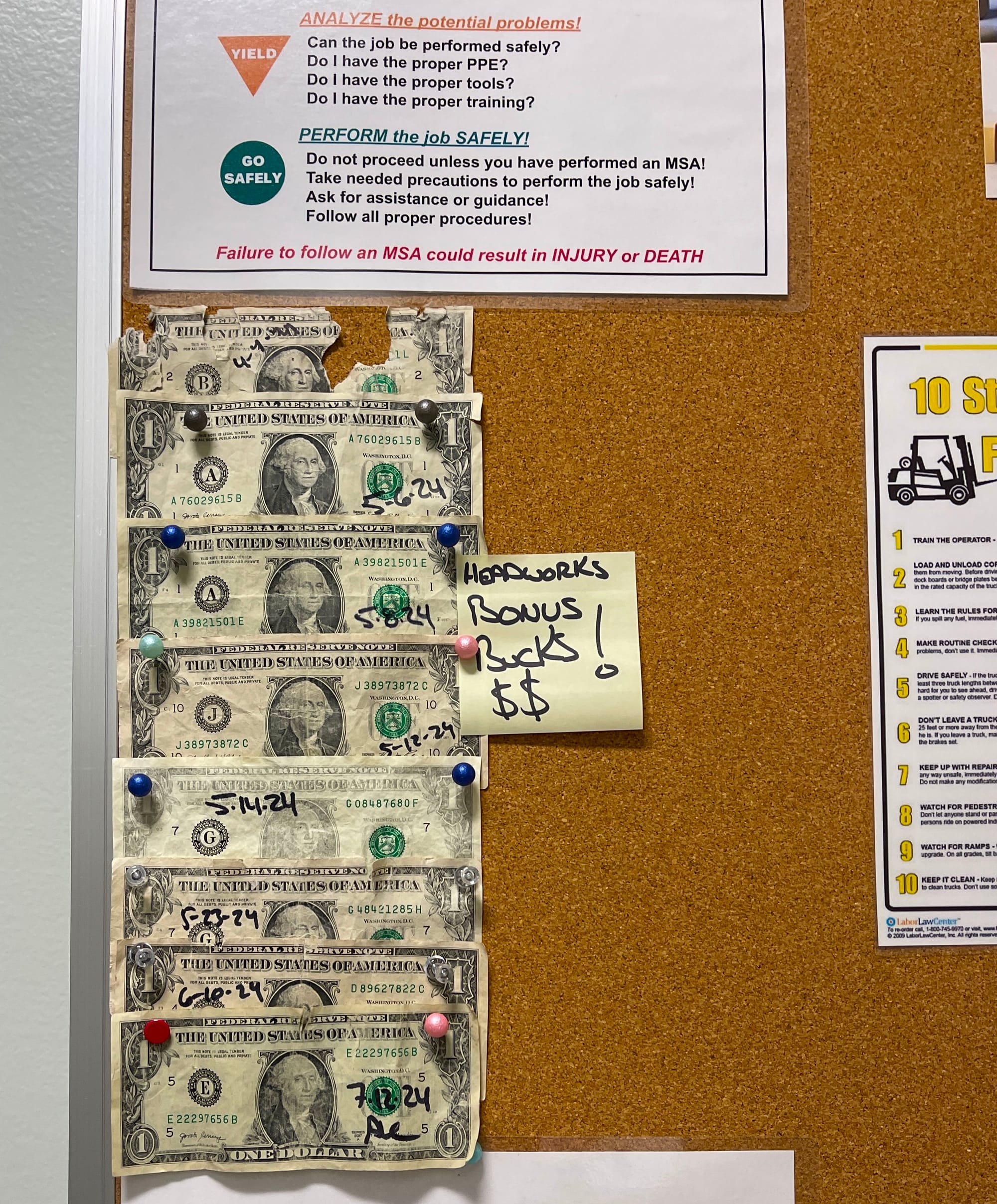

In a nutshell: When wastewater arrives from town — via collection-system pipes and septic-system pumping trucks — and enters the building, it first passes through filters that remove any solid, inorganic matter. Dan and his crew have found golf balls, Airpods, dollar bills (including a $20) and lots of “flushable” wipes — which are not designed to decompose, and clog septic tanks and pipes as well as municipal wastewater collection systems.

The remaining liquid, known as “influent,” goes into large aeration tanks and gets mixed with “activated sludge” — liquid that includes certain microorganisms and more wastewater. This aeration process — called a “Sequencing Batch Reactor” — allows much of the nitrogen from the influent to disperse in gas form and encourages the microorganisms to digest the solid organic waste.

Eventually the solids — which make up a surprisingly small amount (0.5%) of the total intake — are digested by the microorganisms, which over time settle on the bottom of the tanks. Then the solids are removed, thickened further, and ultimately trucked off-Cape, to an incineration facility in Cranston, Rhode Island.

The “clean” water that’s left — again, it’s called “effluent,” and it does look extremely clean! — gets filtered again, UV disinfected, then discharged into one of five “effluent wicks” — 80-foot-deep holes filled with rocks located off Lots Hollow Road.

These five wicks, which each can handle up to 595,000 gallons of water a day, slowly filter the effluent again. After moving through the wick, it seeps through another 40 or more feet of soil and into the aquifer, joining with groundwater in the Monomoy Lens and eventually — because of how the groundwater flows — entering a stream, wetland, or pond and ultimately Cape Cod Bay.

Stormwater

We know precipitation feeds our aquifer, waters our gardens, and keeps our ponds and streams fresh. But storms — especially the fiercer ones that are becoming more common as the climate changes — can bring more precipitation than our grass, ponds, sand and soils can absorb.

Where does it go?

An ad hoc network of private and public stormwater drains and catch basins — dating back to the 1950s or before — diverts storm runoff to underground pipes, catchments, and outfalls. According to the Orleans Department of Public Works (DPW), we have approximately 1,500 storm drains or catch basins with 117 outfalls — the large, open-mouthed pipes you might have noticed along the shores of Town Cove, Skaket Beach, or Meetinghouse Pond. While properties on the many private roads in Orleans are responsible for their own stormwater management, the municipal catch basins are cleaned twice a year, in the spring and fall, some on a rotating basis, to prevent clogging and prevent detritus from washing into coastal areas. (At Town Meeting in May, voters approved the purchase of a new catch basin truck which will allow the DPW to clean more basins more often.)

Stormwater often contains industrial chemicals and waste — gasoline, wiper fluid, pesticides, herbicides, fertilizers, pet and wildlife excrement, even hazardous paints and solvents that have been illegally dumped — that enter the surface water (our ponds, streams, wetlands, estuaries and bays) completely untreated.

Orleans’ Stormwater Bylaws require property owners to divert stormwater to areas covered with vegetation on their property and keep it there (while also keeping it away from wetlands). Draining stormwater directly onto public roads is also prohibited.

You can learn more, including what you can do to manage stormwater on your property, by checking out the Association to Preserve Cape Cod’s Stormwater Management Fact Sheet. We also recommend taking a look at Orleans’ recently updated Stormwater Management Plan, which includes a map of the drainage system.

Estuaries

Estuaries are places where freshwater meets up with the ocean. Brackish — meaning a mix of salt and freshwater — estuaries are often called the “nurseries of the sea,” because so much wildlife spawns and grows in them. They’re essential to the health of the ocean, and therefore to the health of our planet. In Orleans, our estuaries are Pleasant Bay, Skaket/Namskaket/Little Namskaket Marsh and Nauset Marsh, which includes Town Cove, Rachel Cove, Woods Cove, Roberts Cove, and Mill Pond as well as Salt Pond in Eastham. In addition to being valuable ecologically, these places are economically — and spiritually — vital to Orleans.

They are also fragile.

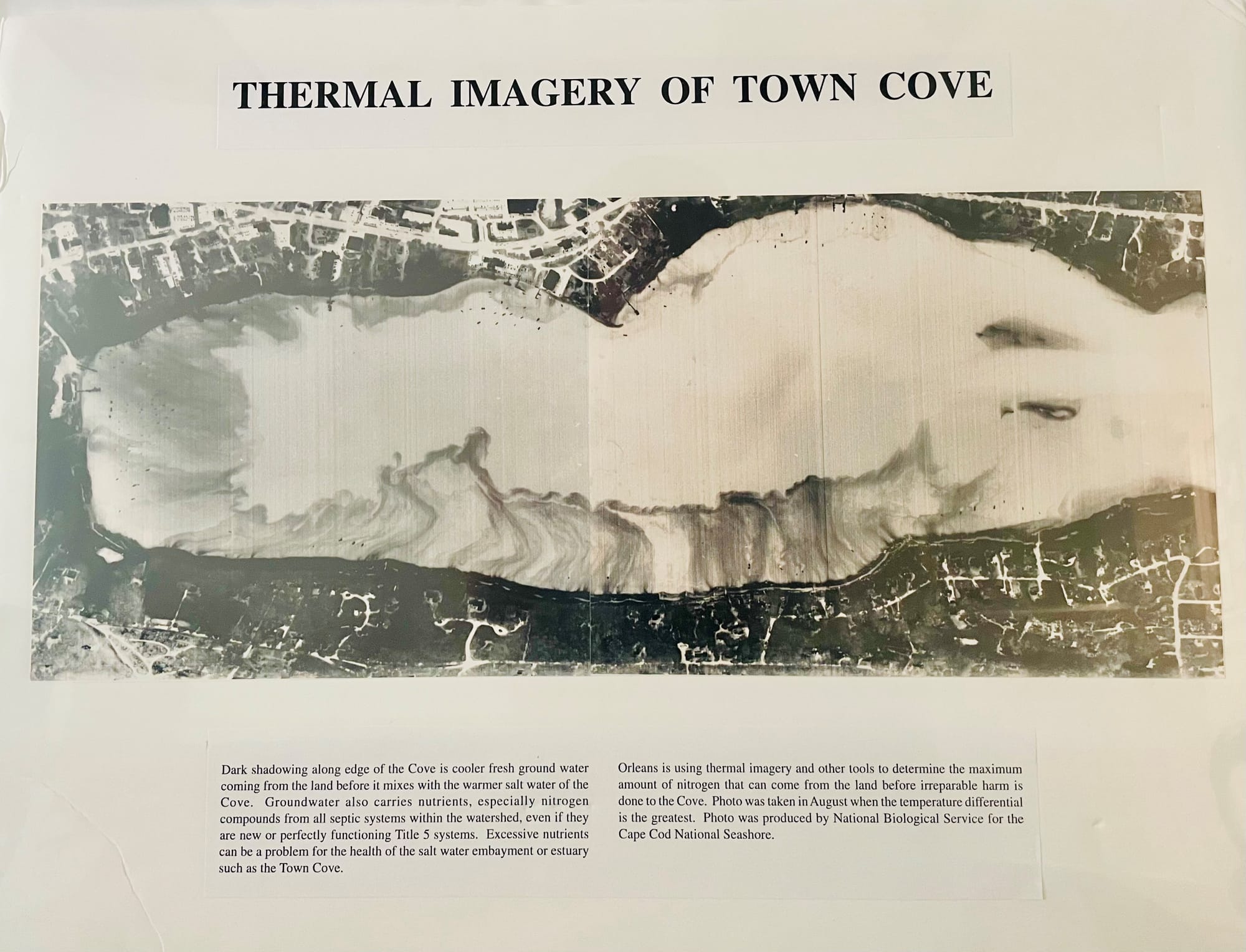

Areas like Nauset Marsh, because they are semi-enclosed, relatively shallow and have a lot of shoreline, are particularly susceptible to pollution, especially from nitrogen, a key nutrient in human and animal waste as well as fertilizer. Add in our permeable, glacial soil and we’ve got serious problems.

What kinds of problems?

Excess nitrogen problems. Nitrogen breeds algae and bacteria, which not only are unpleasant and sometimes toxic, but also consume oxygen. Low oxygen in the water makes it hard or impossible for eelgrass, fish, shellfish, and wildlife in general to survive. It’s a cycle of ecological and economic loss that will not rectify itself.

According to a Cape Cod Commission report, “the ability of most Cape Cod coastal embayments and estuaries to assimilate nitrogen has already been exceeded.”

Since 2001, the Massachusetts Estuaries Project (MEP) has been studying estuaries around Massachusetts to assess their health. The study — which analyzed factors including eelgrass loss, oxygen levels at various depths, and the amount and diversity of marine life, especially in the deepest spots — found that Cape Cod Bay (Namskaket Marsh and Rock Harbor in Orleans), Pleasant Bay Estuary (Meetinghouse Pond, Lonnie’s Pond, Arey’s Pond, Pah Wah Pond, and Pochet Inlet, in Orleans) and Nauset Estuary all require remediation.

Parts of the Pleasant Bay system and Nauset (especially Town Cove, Roberts Cove and Mill Pond) have lost almost all of their habitat and much of their wildlife.

Protecting Wetlands

In Orleans, we have both coastal and inland wetlands. Coastal wetlands include beaches, tidal flats, salt marshes, dunes, and coastal banks (some of which exist inside estuaries).

Inland wetlands are low points in the topography where groundwater seeps in from below. Sometimes they’re wet all year, like swamps and marshes, and sometimes they appear dry but fill with groundwater periodically — these are called “vernal” ponds. They’re especially sensitive spots, ecologically speaking, because they are places where groundwater comes into direct contact with surface water.

Wetlands have long been undervalued — regarded as unsightly, mosquito-breeding swamplands, and used as cranberry bogs (which involved extensive use of insecticides), drained, or filled in for development or other industrial uses. Since Colonial times, more than half the wetlands in the U.S. — including almost one-third of the wetlands in Massachusetts — have been destroyed.

This tide has started to turn. In the 1960s, Massachusetts began protecting wetlands, leading to the Wetlands Protection Act of 1972, which defines different types of wetlands and regulates what kind of work can be done in or near them.

Who administers the Wetlands Protection Act in Orleans?

The Orleans Conservation Commission. It is responsible for ensuring that any work to be done within 100 feet of a wetland — fresh, salt, brackish, and vernal ponds — complies with State regulations. (Read the Commission’s full charge and their brochure which includes information and guidelines for Orleans residents.)

Drusy Henson currently chairs the Commission. She says individuals can make a big difference in protecting Orleans wetlands. For starters, she suggests that property owners consider creating a “vegetative buffer” — planting trees, bushes, and grasses — between themselves and the water. A vegetative buffer provides habitat for wildlife and absorbs storm runoff — and the pollution that comes with it — before it gets into our water.

She also suggests choosing native plants when possible — “anything that doesn’t need much water is a good thing,” she says — and avoiding pesticides and fertilizers, especially close to wetlands. Pesticide use is prohibited within 100 feet of wetlands, as are most uses of herbicide.

Next Steps in Our Wastewater Plan

No discussion of water in Orleans would be complete without a status report for our epic Comprehensive Wastewater Management Plan (CWMP).

How far along are we?

Phase 1, The Downtown Area, is complete. (The town provides helpful information on connecting, including financial resources available to property owners, on its website. Also, great news: there have been recent changes in the MA tax code that offer major benefits to property owners looking to upgrade septic systems or connect to the wastewater collection system. Read a description of the changes from Association to Preserve Cape Cod Executive Director Andrew Gottlieb.)

We are now in the midst of the construction portion of Phase 2, the Meetinghouse Pond Area, which will make the wastewater collection system available to another 500 Orleans properties and is projected to finish in late fall 2025. (See construction details, including a 3-week “look-ahead” detailing construction activities and detours.) When complete, these first two phases will connect approximately 1,400 residences and businesses in town to the wastewater collection system.

That brings us to Phase 3, the Lakes and Ponds Area. Approved at last spring’s Town Meeting, it’s in the preliminary design phase and currently includes 384 parcels. For a little more information, here’s the Cape Cod Chronicle’s coverage of last year’s update to the CWMP, which also includes aquaculture and permeable-barrier pilot programs as possible additional nutrient-reduction strategies.

When will we see some results?

The town’s water woes are centuries in the making. We’ve finally begun turning the ship around, but seeing measurable outcomes could take some time. According to water scientist Ed Eichner, we will likely see lower nitrogen loads in the Meetinghouse Pond Area first, since that entire area is being connected to the wastewater collection system and includes not just Meetinghouse Pond, but several of the saltwater ponds that are currently some of the most compromised.

Things could get worse in some areas before they get better, Eichner warns, because zoning and occupancy has fluctuated since studies were done. There’s also a delay between when nutrients enter the ground and when they show up in the water — as long as 10-15 years in the case of some inland leach fields.

One encouraging note: improvement in the quality of Town Cove should lead to improvement in the further reaches of the estuary — in particular, Roberts Cove and Mill Pond, which aren't slated to be connected to the wastewater collection system for many years but which take in water from the inlet.

Do we need to worry about excess nutrients in our drinking water?

Eichner says no. Humans can tolerate much higher concentrations of nitrogen and phosphorus than our ponds and estuaries.

In the meantime, we can do our best to be patient with the noise, construction mess, and detours caused by the wastewater project, focus on additional water-protection efforts — and keep testing.

Keeping Tabs on Our Water

Our water — drinking, pond, and coastal — is monitored on a regular basis. This is done for residents, visitors, commercial and recreational fishing, as well as research that the Commonwealth conducts to study trends in water quality.

Here is some of what’s going on:

The Orleans Water Department tests the groundwater that supplies our municipal drinking water regularly, in accordance with Federal and State parameters, both before and after treatment. Test results are published annually.

The Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries tests for red tide and other natural contaminants. You can find closure notices here. The Barnstable County Department of Health and Environment tests public bathing beaches — including Nauset and Skaket Beaches, Pilgrim and Crystal Lakes — weekly for fecal matter, or E. coli and enterococcus. Closures are posted weekly on the Barnstable County website. Provincetown’s Center for Coastal Studies conducts water quality testing in Cape Cod Bay and shares results mapped by location. The Association to Preserve Cape Cod, in partnership with the Orleans Pond Coalition, monitors six ponds in Orleans (and many more all over the Cape) for harmful algae or cyanobacteria from late May through the end of November, with results posted weekly

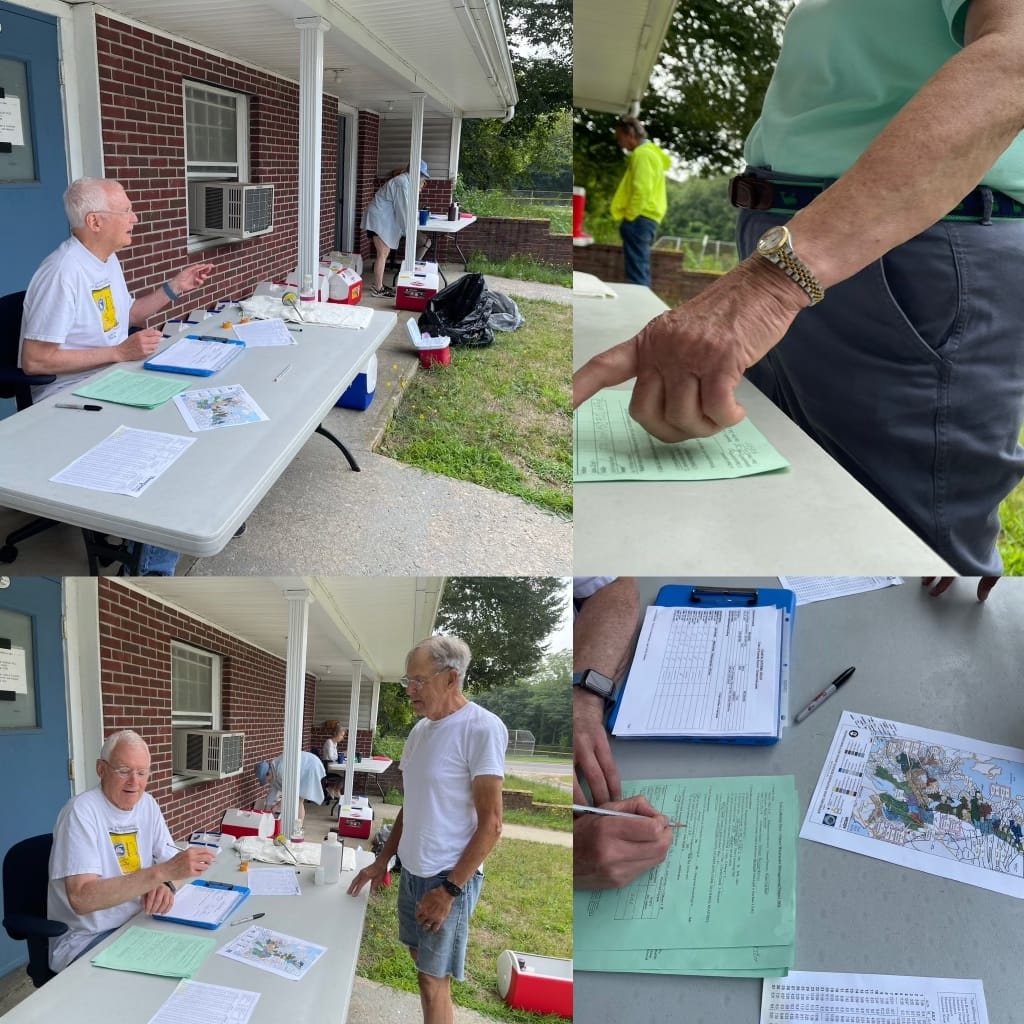

Locally, a group of 50 volunteers, coordinated by the Orleans Marine & Freshwater Quality Committee, have been collecting samples from 26 different sites in Orleans every summer — 12 sites in Nauset Estuary, 14 sites in Pleasant Bay — for an ongoing study of nitrogen levels. This comprehensive sampling began in 2001 to support the Massachusetts Estuary Project, with the goal of quantifying pollution levels, determining the best way to reduce them, and ultimately returning the estuaries to their natural productive capabilities.

What’s the trend since 2001?

“Increasingly poor water quality,” says Rich Levy, the Chair of the Marine and Freshwater Quality Committee. “As the local population has grown, the impact on our ecosystems by land development activities has increased, and now the mitigation projects, such as sewering, are not far enough along to make a difference that is measurable. As more of the Town is sewered, we should see better results in our waters. The good news is that Orleans is ahead of the curve in part due to the ongoing efforts of our water quality sampling volunteers.”

What Can You Do?

The Orleans Pond Coalition (OPC) has lots of good ideas. You can take the “H2Orleans Pond Pledge” by not using pesticides and fertilizers in your garden, supporting the town’s ongoing comprehensive wastewater project, and “embracing a Cape Cod Lawn” in all its clover-heavy, hodgepodge glory. In the OPC Blue Pages, you’ll find a comprehensive list of ingredients in household cleaners and other products that are the most harmful to the watershed and should be avoided.

The Orleans Conservation Trust’s At Home with Nature program has even more resources for making your yard nature-friendly.

This month, the Marine & Freshwater Quality Committee needs one more volunteer to help with sampling. For 2025, the committee is looking for volunteers who own and captain boats with access to Town Cove and Nauset Estuary and/or Pleasant Bay, as well as additional volunteers who could help with water sampling on board. If you’d like to volunteer, complete the Town of Orleans Citizen Interest Form and send it in.

On September 13-15, the OPC will be sponsoring its annual “Celebrate Our Waters” Weekend. This year they’ll be offering a tour of the new Wastewater Treatment Facility, along with sailing on Pleasant Bay, kayaking tours of Town Cove, birdwatching at Skaket, and much more. Reservations are required for some activities; see the full schedule.

Just this week, the Association to Preserve Cape Cod was awarded a $15 million grant from National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to support planning, design, and implementation of five wetland restoration projects on Cape Cod, although none in Orleans.

Many community groups are involved in water quality, water awareness, and studying the impacts of climate change on water. If you’d like to find a way to be more involved, here are links to their websites:

Association to Preserve Cape Cod

Cape Cod Commission’s Water Resources Division

Cape Cod Groundwater Guardians

Orleans Energy & Climate Action Committee

Orleans Marine & Fresh Water Quality Committee

With so many groups involved in protecting water quality, a new one, Orleans Climate Action Network, has a mission to coordinate and share information.

Acknowledgements:

EXIT 89 is grateful for the help and guidance of many town employees, experts and committee volunteers. Special thanks to: Cil Bloomfield, P.E.; Susan Brown and the Orleans Water Department; water scientist Ed Eichner at TMDL Solutions; John Jannell, Orleans Conservation Agent and Kristyna Smith, Orleans Conservation Clerk; Carolyn Kennedy and Rich Levy, the former and current chairs of the Marine and Freshwater Quality Committee and board members of the Orleans Pond Coalition; George Meservey and the Orleans Planning and Development Department; Kelly Messier and the Orleans Health Department; Dan Sullivan-Xenos and the Orleans Wastewater Treatment Facility; and Rich Waldo, Orleans DPW Director.

EXIT 89 is an independent publication. Our mission is to help Orleans voters make sense of town issues by providing a clear and impartial overview of the latest developments. We want to help fill the current information gap, reduce the "mystery" of Town Meeting, and promote vibrant civic engagement.

Our hyperlocal digest is researched and written by journalists Martha Sherrill and Emily Miller. Elaine Baird and Lynn Bruneau are the founding advisors. We are all residents of Orleans. Infographics, and tech support are provided by Kazmira Nedeau of Sea Howl Bookshop.

Our digest is 100% free — and we aim to keep it that way. If you find what we do valuable, please consider supporting us. With Lower Cape Television (LCTV) — a 503(c)(3) — as our fiscal sponsor, all contributions are now tax deductible. Donations by a check made out to "EXIT 89" will save us a processing fee. Please send these to EXIT 89, P.O. Box 1145, Orleans, MA 02653. To donate online, click here.

As always, we’d love to hear from you. Readers have enriched our understanding of Orleans — and sharpened our focus. Please share questions, comments, and ideas for future issues at hello@exit89.org. And if you are new to EXIT 89, take a moment to sign up for a free subscription.