“Whose woods these are I think I know

His house is in the village though.”

–Robert Frost

This spring, some Orleans walkers were flabbergasted one morning to find a large fence and NO TRESPASSING / VIDEO SURVEILLANCE signs standing between them and one of their favorite waterfront walks – Weeset Point. Reactions on social media and heard around town ranged from incredulity (“Can they really do this?”) to anger (“How dare they do this!”) to sadness (“I cried myself to sleep. . .”) to resignation (“If I owned waterfront property, I’d probably do the same thing.”)

The fence closes off a point of land that was populated for thousands of years by Indigenous people, going back to at least 4000 B.C., and home to a teeming Nauset village when French explorer and cartographer Samuel de Champlain arrived in July 1605. After the Nauset were killed in large numbers by diseases spread by colonists, it eventually became a pasture where cows grazed with a view, and more recently, a quiet beloved spot for walkers, boaters, birdwatchers, and a few lucky property owners. How and why the fence at Weeset Point came to be is something you can read about in the Cape Cod Chronicle.

The fence is an anomaly, the only one to be found along all 50 miles of saltwater shoreline in Orleans. Over the last century, despite a major population influx to Cape Cod, private owners and the public have managed to coexist peacefully, remarkably so. There’s a long tradition here of sharing the shoreline amicably. But with even more people, and so much waterfront in private hands — nearly 700 properties on saltwater and 200 on freshwater ponds — it seems like a good moment to review some basics.

What are the rules — and what do they mean for you?

In this deep dive, EXIT 89 offers an explanation of what’s public and what’s not in Orleans: beaches, trails, ponds, marshes, town-owned conservation areas, town landings, and Orleans Conservation Trust (OCT) land. We’ll explain the rules of engagement. We’ll look at a few examples of what can happen when those rules are ignored. And finally, we’ll offer suggestions for how to move forward in the tradition of respectful co-existence, avoiding conflicts and undesirable outcomes in the future.

WHO OWNS THE SHORELINE?

Let’s start with the unadorned, perhaps unwelcome, truth: Most land in Orleans doesn’t belong to you. But it does belong to someone.

Saltwater (or tidal) waterfront. Let’s start there. Orleans has about 50 miles of it. Running a close second in terms of most shoreline miles — Chatham has 66 — there is no comparison when it comes to the quality of our spectacular public beaches. But most of the saltwater shoreline in Orleans — about 90 percent, divided into 635 waterfront parcels — is privately owned. You’ll find a slightly lower private to public ratio for freshwater ponds. There are 181 privately-owned freshwater pond-front properties in Orleans, with 20 percent of that shoreline owned and managed by the OCT or town. This link will take you to a Dropbox folder of Town Assessor Brad Hinote's breakdowns of shoreline miles, property owners, and a map of Orleans waterfront.

The upshot: as attached as you might be to your favorite walk—that marsh! that view! the way the light hits the water at 4 PM! — the reality is, you are a guest at someone else’s party. It doesn’t matter if you happen to own a waterfront parcel nearby, or even next door. It doesn’t matter if you’re a native, a washashore, or a vacationer — or how much your dog loves splashing through the eelgrass and eating dead crabs.

Dear nature-lover, you are walking on private property, even if you have no idea who the owner is — an individual, a family trust, an LLC, or the OCT. You may see signs posted with rules: Keep Dogs on Leash. Marsh Under Repair. No Trespassing. . . They are inconsistent, and can seem random. That’s because what the signs say, and whether to post any signs at all, is entirely up to the owner. And you — as their guest — are obliged to obey them, assuming it’s a party you’d like to continue to attend.

Let’s explain why.

OLD LAWS, NEW PROBLEMS

Unlike in most coastal states, where private property on the waterfront extends to the mean high-tide mark, waterfront property in Massachusetts extends to the mean low-tide mark. This is because of a set of laws, called the Colonial Ordinances, enacted between 1641-1647 and still in effect today.

Back then — and up until relatively recently — private citizens weren’t particularly interested in owning waterfront property. The era of tourism, suntans, surfing, dog walking, and seaside holidays was still a long way off. The Colonial Ordinances were an effort to make owning the shoreline more attractive, particularly to wharf and boatyard builders, which Massachusetts sorely needed to attract.

This leaves Cape Cod and the Islands with special challenges around public access. On Nantucket, a lot of work has been done by the town, property owners, and private conservation groups over several decades to provide as much public access to the shoreline as possible; about 50 percent of its shoreline is publicly accessible (much more than Massachusetts as a whole, of which only 12 percent is fully accessible). But on Martha’s Vineyard, many of the best beaches are off-limits to the public or visitors. Resident stickers are required for town-owned beaches and others, the so-called “key beaches,” require private ownership; one may purchase (or more often, inherit) a slice of property, or sometimes a share in an association, that owns a private stretch of beach, accessed only by a padlocked gate. These keys can sell for as much as $435,000. Here on Cape Cod, the creation of the Cape Cod National Seashore has kept much of our shoreline both open to the public and protected.

The Ordinances, which apply to all privately owned saltwater shorelines, do make exceptions for three specific activities in the intertidal zone, that strip of sand between the low and high tide lines: fishing, fowling, and navigation. The exact language can be found on Massachusetts' government website.

What the Ordinances do not allow for is general recreation — walking, dog-walking, jogging, sunbathing, picnicking, swimming, etc.

It’s possible this could change. Last year, State Senator Julian Cyr (D-Truro) and State Representative Dylan Fernandes (D-Woods Hole) led a push to make beach access laws less restrictive in Massachusetts by proposing legislation that adds the word “recreation” to the list of allowable activities between the low and high tide lines.

While the bill has advocates through-out the Bay State, it may fall short in making its case in the courts, even if it passes. Other beach access activists suggest a different approach: the Commonwealth or town governments buy the intertidal zones or claim them through eminent domain.

Have an opinion? Give Senator Cyr or Representative Fernandes a call.

MORE PEOPLE, MORE PROBLEMS

The population growth and exuberant rental market in Orleans has been a mixed bag, economically speaking, for our town. (EXIT 89 has written about the downside of rising real estate prices, and the related housing shortage that prevents many from affording homes here.)

Another consequence of more people is heavier use of our natural spaces — shoreline paths, landings, and woodland trails. We live in a time of passionate outdoor exercising, nature-loving, and support for local conservation efforts. While more and more land is acquired by conservation, and opened up to access, geolocation technology helps anyone with a smartphone find their way to places that were once un- or little-known.

The strain is felt on more than just our natural spaces; when homeowners find themselves living in what feels like a public park, conflicts can arise. The good news? Considering how much of the shoreline in Orleans is private, and how many people and dogs are enjoying nature these days, there have been remarkably few clashes. But examining those that have occurred can, we hope, help avoid similar situations in the future.

WILDFLOWER LANE

Until recently, Wildflower Lane was a much-loved, under-the-radar spot near Skaket Beach. Residents parked in a residents-only dirt lot beside the Bay, crossed the beach owned by properties on Willie Atwood Road, and let their dogs run free on the tidal flats. How glorious! For some…

Then residents complained that dogs were out of control and that their humans were trespassing. Which brings us back to the Colonial Ordinances: private property extends to the low-tide line, or in a case like the flats, “100 rods” (1650 feet). Even though dog walkers were parking legally, they were crossing private property to get to the flats. When the owners’ rights prevailed, dogs were banned.

Incredulous dog owners and property owners alike rallied together and lobbied the Select Board — to keep Wildflower Lane and the beach there open for dogs. After much negotiating, some of it pretty heated, a new set of regulations was established in 2019: in summer, dogs are allowed on the beach before 9 AM and after 5 PM. They can be off-leash once dogs are at least 300 feet below the high tide line.

We could write a whole issue — a long one — on dogs in Orleans. And we may someday. But for now, suffice it to say the rules for dogs on town beaches, as well as at Crystal and Pilgrim Lakes, vary by location (spelled out here). At most popular dog-walking spots, you’ll find boxes stocked with Mutt Mitts, generously provided by the Orleans Pond Coalition. Signs at each spot also tell you dates and times you can bring dogs along. The Select Board determines most of the opening and closing dates for dogs on Orleans beaches and ponds. The exception is Nauset Beach. Unlike several other town beaches within the National Seashore, where leashed dogs are permitted year round, Orleans has developed a Habitat Conservation Plan (HCP) for Nauset that protects nesting shorebirds listed as threatened species under both the U.S. Endangered Species Act and the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act. Due to the nesting birds, and other concerns, dogs are prohibited on Nauset from April 1 to October 15.

One noteworthy nugget: There is no leash law in Orleans. On public property, dogs are required only to be “restrained,” and that can mean by voice control. On private property, owners are free to require leashes on their land and frequently do. Same goes for the Orleans Conservation Department and private non-profits like the OCT.

HENSON’S COVE

Dogs are forbidden at Henson’s Cove — formerly known as White’s Lane Trail — which occupies 17 acres of donated and purchased land, including prime nesting spots for the threatened Northern diamondback terrapin adjacent to The River. Abutters and other neighbors donated and helped raise money for the conservation effort, with the hope that the path would not become too popular and overused.

The mission of the OCT is to “preserve land and educate the public in order to sustain our natural resources and the character of our community for generations to come.” But with demographic shifts bringing more walkers to Orleans trails, and more dogs, some question if encouraging access to a sensitive habitat might actually be insensitive.

“OCT’s approach is to have managed access,” says Kevin Galligan, Trustee and President of the OCT board, as well as member of our Select Board. “We are actively monitoring our conservation lands, not just human activity but wildlife. We desperately try to explain to the public how to use the trails, and we restrict the number of parking spots to keep the numbers low.”

Sharing nature is a time-honored and “genuine Cape Codder way of being,” Galligan notes. But he concedes that getting the balance right — between sharing the land and protecting it — can be tricky.

Similarly, the Town of Orleans has a Conservation, Recreation, and Open Space Plan, with a three-pronged mission: conserving Orleans' natural resources, preserving its open space, and “providing ample opportunities for recreation for its citizens.” These are each worthy and important but sometimes at odds with each other.

In the case of Henson’s Cove, and other OCT properties, neighbors are encouraged to report storm damage, overcrowded parking areas, and any rule-breaking. Volunteer land stewards make site visits to make sure trails are maintained properly, boundaries are not encroached, and that land is being used appropriately. If you are using an OCT trail and see encroachment issues, tossed garbage, fallen trees, cleared vegetation, vandalism, signs of campfires or anything else concerning, you are encouraged to call OCT at (508) 255-0183 or email oct@orleansconservationtrust.org. There are also property monitoring forms online to note your observations, from invasive species overgrowth and erosion to wildlife sightings.

BAKERS POND

Orleans has 63 freshwater ponds covering 220 acres, with six miles of frontage. The rules of ownership depend on the pond’s size: if it covers less than 10 acres, private property rights extend to the middle of the pond. If the pond is 10 acres or more, it’s considered a “Great Pond” and the entire pond is owned by the public, and the state is required to provide “reasonable access” to the water. (Private property on the shore of a Great Pond ends at the mean highwater mark — basically, the waterline, since ponds aren’t tidal.) Orleans has four Great Ponds: Pilgrim Lake, Crystal Lake, Cedar and Bakers Pond.

Both Crystal and Pilgrim Lakes have town-maintained swimming areas open to the public, and public beaches, parking, and benches. As a public swimming spot, the water is tested every week. (Results of additional testing for cyanobacteria can be found here.)

Things are a little different at Bakers Pond, and show how nuanced the words “public access” can be. In the 1700s, the classic kettlehole pond with a sandy shoreline had one owner: William Baker. Over the next three centuries, the shoreline was sold off in smaller and smaller parcels, and eventually the site of a subdivision in the 1970s. The 1250 feet of shoreline has 14 private owners now, along with the MA Dept of Fish and Game, the MA Highway Dept, Orleans Conservation, and the Brewster Conservation Trust.

There are two unpaved parking areas by Bakers Pond, and a small sandy beach designated for boat launching. And despite the prominent NO SWIMMING signs posted by the State of Massachusetts, on most days in the summer, you will see a few swimmers, some sunbathers, and maybe a family of picnickers, enjoying a moment of old fashioned Cape Cod quiet.

The truth is, people have always enjoyed swimming at Bakers Pond, including many of the shorefront owners. But they do so at their own risk. A pond that is stocked with fish, and designated for fishing and boating — paddling, rowing, and electric-powered boats only — Bakers has never been an official “bathing beach.” There have been various iterations of a NO SWIMMING sign since the 1980s. Currently, there are no lifeguards or restrooms or weekly water quality testing (for Enterococci or E. Coli) by Barnstable County, which would be standard at a designated public swimming beach.

Swimmers also risk ticking off the people who are fishing — and who have every right to call Massachusetts Environmental Police and ask for their removal.

That rarely happens at Bakers, though. It’s a peaceful spot. And the property owners hope to keep it that way. Their signs are polite. Please Respect Private Property and Preserve Our Fragile Ecosystem. According to Ron Mgrdichian, President of Friends of Bakers Pond and a shoreline owner for 30 years, unruly dogs and children are the most frequent problems, and occasional moonlit partying by teens. The Friends’ intent is to protect the pastoral quality and natural habitat, and a rare and lovely wildflower that blooms this time of year, the Plymouth Gentian.

A bill in the Massachusetts Legislature sponsored by Sen. Julian Cyr and Rep. Sarah Peake proposes to turn the pond into a “public bathing beach,” a change that Mgrdichian says would require more parking, more frequent water testing, port-a-potties, trash containers, and seating. Is that a good idea? The Friends of Bakers Pond aren’t the only ones who aren’t sure.

WHERE CAN I WALK?

“Baby I’ll be there to shake your hand,

Baby I’ll be there to share the land.”

--The Guess Who

If you’d rather not navigate the intricacies of private property, don’t be discouraged: there’s almost 1000 acres of open space in Orleans,

Open space falls into a few categories:

Town Beaches: Some of the best beaches in the world, both Nauset and Skaket Beaches are open to walkers year-round and to dogs during the off-season. Parking stickers are required between 7:30 AM and 4 PM. Click here for information about access and stickers. And, just for fun, here is a link to beach webcams.

Town Conservation Areas are publicly-held open spaces. The Orleans Conservation Department manages a total of 275 acres for public use, offering thirteen areas of maintained trails, a few swimming beaches, and parking. Signs at each area tell you the rules for use.

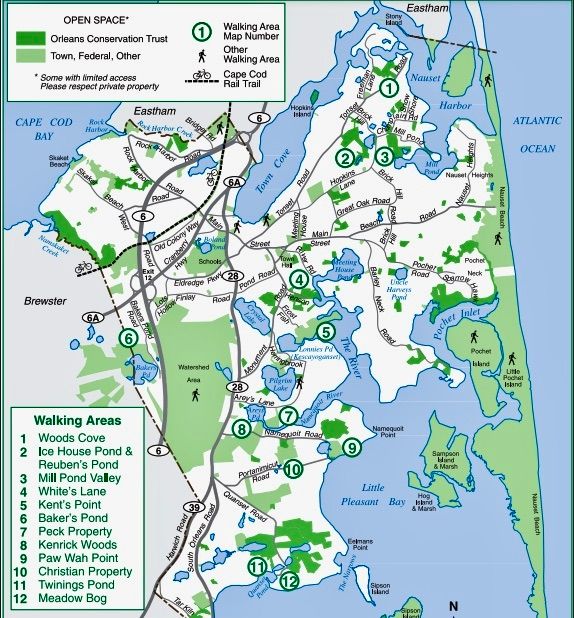

The Orleans Conservation Trust (OCT) — not to be confused with the Orleans Conservation Department — is a private non-profit that owns 660 acres of open space, much of which welcomes the public. Seeking to make improvements to its six walkable properties, OCT has added kiosks, trail maps, and designated parking areas. The trails at Twinings and Icehouse & Reuben’s Ponds can handle more traffic and have four or five parking spaces; the trail at Meadow Bog, like Henson’s Cove, has only two. Signs at the kiosks explain the habitat and efforts to protect it.

Town landings: Orleans has 29 town landings, all of which are public. Or, at least, the landing itself is public. But be aware, the land directly on either side of the landing is often privately owned. In some cases, signs will alert you when you’re entering private land or have reached the END OF TOWN PROPERTY. Currently, four town landings — Priscilla Beach, Doane Road, Cove Road, and River Road — require residential beach stickers to park legally in summer months, and parking restrictions are enforced. There are also seasonal parking restrictions at some landings.

Important tip: If you see shellfishing trucks parked on the beach at a landing, that doesn’t mean you can do it too.

Onward, Together

Our goal at EXIT 89 is to help Orleans citizens and visitors move into a harmonious, nature-rich future. Here are some ideas about ways the town could help:

● Expanding requirements of parking stickers at busy town landings

● Instituting fees for non-residents at crowded spots like Kent’s Point

● Providing trash cans at popular walking areas

● Wellfleet has a Rights of Public Access Committee. Should we?

● And how about a dog park to take pressure off our shorelines?

And, last but not least…personal responsibility. At the end of the day (and the deep dive) peaceful co-existence depends on the behavior of individuals. Next time you’re out walking, be sure to:

● Stay on designated trails

● Leave no trace of your visit — pack it in, pack it out

● Avoid becoming part of the seasonal crush on shoreline trails

● Keep your dogs under control + always pick up poop (And please do not leave the poop bags on the ground!)

● Read the signs that outline the rules of each place you are visiting (Then obey them)

Hopefully, with more information, a little effort, and a healthy dose of respect for our neighbors, we can continue to share this place we are lucky enough to call home.

Special thanks to Brad Hinote and the Town Assessor's Office, Nate Sears and the Harbormaster's Office, Kristyna Smith and Orleans Conservation, Alex Bates and Kevin Galligan with Orleans Conservation Trust, Ron Mgrdichian and Friends of Bakers Pond, for their invaluable help with this issue.